Evangeline Morris | Investigating the Upper Urr Peatland through Extended drawing | Micro Commission July – August 2023

EXTENDED DRAWING:

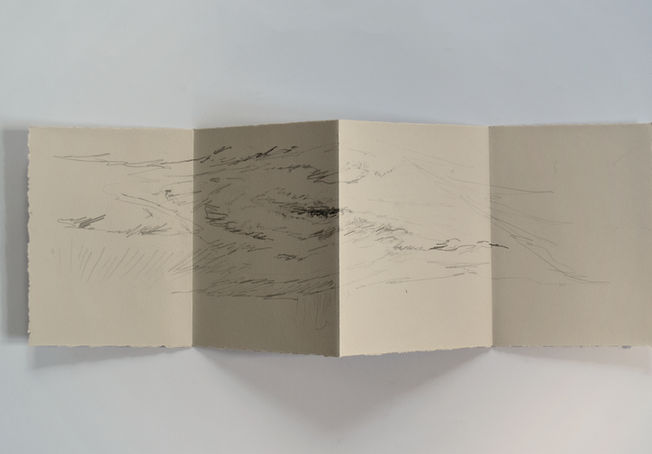

Drawing as a Practice Inclusive of Walking, Writing, Sketching and Visual Practices.

Four And A Half Thousand Years…

Earth Map… detail with translation. Photo Evangeline Morris

Evangeline Morris explores what it means to engage with landscape through an extended practice of drawing that includes walking and other visual methods as a record of time, recognition of place, and an enabler for a deeper more focused encounter with place and land.

For six days Evangeline emersed herself in the Upper Urr peatland feeling the peatland through her footsteps as she trod amid mosses and low lying flora and walked along drainage ditches. Open to the expanse and focusing in on detail she utilised drawing and text to convey a forming relationship with the landscape.

Back in her studio Evangeline further developed her peatland experience, etching into copper plate and creating a vitrine with Earth Maps… and peatland curiosities.

The Upper Urr peatland is a site of community interest. In 2022, Corsock village residents founded the Upper Urr Environment Trust (UUET). Given the local interest in the site and their commitment to improving and managing the habitat, UUET and the local community welcomed Evangeline’s creative explorations.

The Upper Urr peatland was surveyed by CCC in 2023 for potential peatland restoration. The extent of degradation - eroding drainage ditches releasing carbon stored in the peat and drying out the peatland - qualified it for Peatland Action restoration. The restoration work, which is hoped to be underway in 2024, will include the blocking of drainage ditches to halt the flow of water off the peatland, ultimately, rewetting the peat and restoring the bog, and re-locking the carbon in the ground – where it belongs.

Earth Map… detail with translation. Photo Evangeline Morris

Evangeline’s micro commission has captured the site’s quality as seen, surveyed, experienced and recorded through the lens of an artist, prior to the restoration.

Four And A Half Thousand Years is available, on loan, to environmental organisations concerned with peatland restoration, management and conservation: email info@carboncentre.org subject Four And A Half Thousand Years.

Reflecting on:

Four and a Half Thousand Years Deep

Drawing the interruption of our archival Peatlands.

By Evangeline Morris

This is an account of my journeys through wetlands. Of the felt, seen and understood experiences of my brief time working at the incredible peat bog leased by the Upper Urr Environment Trust (UUET), near Corsock in Dumfries and Galloway.

This residency was an intense and deeply moving period of time discovering the unique environment that is a peatland bog. Learning about these places and their actions to store and hold information was starkly contrasted by the surrounding and constant reminders of the precarious situation we have put these vital habitats in.

From historic drainage ditches to recent timber forest planting, these sites are under threat from the affects of human intervention at every angle.

It was a pleasure to be able to draw this site ahead of exciting regenerative work to be undertaken.

My first day on the bog was interesting, and reversed a lot of my preconceived ideas of what I was going to find. I was joined by Peatlands Project officer Lewis Robertson and Peatlands Connections officer Kerry Morrison so that I could learn how to read this landscape, keep myself safe and get a few pointers on the parts of the site most of interest. I must admit, I was slightly nervous of the bog, with its reputation alluding to a fowl smelling, desolate and dangerous landscape that closely aligns itself with death, the decaying and a fear of sinking quickly through the ground never to be discovered. I quickly found that this place was full of life from insects, birds and small mammals to a plethora of plants that filled the landscape with vivid colour of bright greens to lurid oranges, duller umbers, dusky mauves and pink mists that were, much to my surprise, accompanied by sweet, heady fragrances.

We journeyed out into the middle of the bog where Lewis began explaining how peatlands form, are maintained and are monitored. Using a peat probe, we measured the depth of the bog, which started at about 50cm close to the grassy edges, but quickly got deeper as we moved into the centre until we felt the crackling of gravel 4 and a half meters below our feet through the handle of the probe. This is deep enough to cover a double decker bus. This part of the bog was 4,500 years old, a thousand years for every meter down.

This is literal deep mapped time, preserving in layers a landscape that has been changed and withstood the modifications of human activity, but now presents its history through its own language. My aims of drawing this site, on foot and with pencil, are to become aware of the ways it is talking to us and interpret the languages it uses, to understand what it is telling us about its past and how to negotiate it in the present.

The Trace

My first day on site was mostly about learning how to read it and to show me the sites areas of importance of both health and prosperity, including its degradation from historic use and drainage. Among our conversations we discussed the importance of touch when negotiating a bog as your eyes are easily deceived by the foliage cover, and that actually you are guided far more by the sensations passed through your feet. Lewis noted that he prefers a wellington boot for this reason, as you have more of a gauge about the stability of the ground underneath your feet and are able to more accurately sense your way across the site. I have drawn on a sense of touch within my work before and how you draw the site with this sense of touch in the same way as you do a pencil. Landing lighter or heavier of foot with its rises and falls, delineating the space. However when on a peat bog you are travelling through dense and misguiding foliage, this is far more significant. Because what you see is not necessarily, and almost always not, an accurate gauge of the ground you walk on, you are drawing two very different images at once. The drawing of this landscape is happening from the moment you step on it for a need to relay the invisible, and therefore engagement through your entire body’s movement becomes essential.

Sphagnum mosses are among the most deceptive, stacking high it grows vertically and holds such an incredible amount of water it can be wrung out like a sponge. But, to the naked and unobservant eye it is like any other moss, so when you come across a hummock of it which can sometimes be up to meter tall it can be perceived as a solid and give way with such incredible ease, it feels like it may not even be there at all.

Lewis shows me the LiDAR images that the team use to understand the site, it is like a rubbing of the land, showing its exacting topography and stripping back the visible layer, to reveal the concealed underneath. LiDAR marks out with ease the ditches, hags and historic harvesting sites that are concealed by the plant growth on top. This trace of the land reflects what I am doing as I negotiate the bog, that second image that you are drawing with a different kind of visualising through sensation alone. Interestingly I find the LiDAR to sit in a different category from other forms of mapping I have studied which I have found to be reductive and omitting of integral site specific information, but in this instance it reveals one of the layers to the bogs image that is otherwise not visual. It directly speaks to the experience of walking across this wetland, the process of mentally visualising the haptic.

“The whole bog moves as one. As I sit, I sway like the grasses do and I feel the transferral of movement through the ground”

Evangeline Morris. Taken from one of the earth maps presented as the onsite research for Four and a Half Thousand years deep.

Throughout my time on this bog I am constantly drawing through this sense of touch. It is a way of understanding how this place speaks to us. From the memory foam like feel of the deepest part of this site where movement is transferred through the ground across its 4,500 years deep history, to the duller hollow feeling of the exposed peat surrounding the hags and machinery damage, it is a constant discussion. This discussion is one you learn in order to safely move across this place but also one that tells you how the bog is feeling, if it is happy or if it is struggling to do what it should be doing.

“The base of the bog is very different. It is dry & the bare patches of drying peat speak to its condition.”

Evangeline Morris. Taken from one of the earth maps presented as the onsite research for Four and a Half Thousand years deep.

The parts of the land where the visible matches up with the invisible is where the bog is showing most signs of damage. It is where peat is exposed and dry for any number of reasons, but all connected to human intervention. This is where the ground feels hollow and firmer than the jiggling mattress of the deep peat. It is where I have been documenting the land as it is eroded away into drainage ditches, pulling with it layers of carbon time.

The Hagg

My peat bog is a relatively healthy bog by comparison to most, and although it shows strong signs of lasting damage, the erosion is not as bad as some meaning that the Haggs present are only relatively mini Haggs. A Hagg is a sign of active peat erosion where the water drained from a bog has caused gullies to open up and expose bare cliff like faces of peat. The part of the site I have found richest in conversation is a mini hag at a point where several drainage ditches converge and the pull of this water off of the land is so visual, lines and marks are made where the water draws.

On my first day Lewis and Kerry showed me this point on the site and although we found so many exceptional signs of peat health from the organic matter growing there, the way it was exposed in small cliffs suggested that this is far from healthy. Nearby the site is pitted like a crumpet with bare empty holes suggesting that something is “hydrologically wrong” and that even though healthy vegetation like sphagnum still spread through gullies the peatland is struggling to maintain itself.

“This place is fractured. They dehydrate this living breathing organism; drain it of its life force.

These fractures prevent it from moving as one”

Evangeline Morris. Taken from one of the earth maps presented as the onsite research for Four and a Half Thousand years deep.

The Peat is an archive of thousands of years of carbon history, preserving the semi-decayed backbone of life on the bog where a lack of oxygen has prevented its archive from deteriorating as it grows ever upwards, like its sphagnum mosses.

Movement

I had been relatively fortuitous with the weather over the course of my residency, but my last day on the bog was brief because of bad weather moving in. I could not believe the difference that heavy rain overnight had made when I ventured across in a gap in the rain, and was shocked at what the rainfall revealed about the damage of the drains across the site.

“The water runs from the peat at an alarming rate, leaving the peat exposed”

Evangeline Morris. Taken from one of the earth maps presented as the onsite research for Four and a Half Thousand years deep.

On my previous visits where I made drawing studies of the mini hagg at the convergence of the drainage ditches on site, there had only ever been a trickle of water running through and they had begun to show signs of drying from little cracks and fissures in the peat cliffs. The recent rain gushed through these gullies in strong streams and had shifted the earth a noticeable amount around where I had previously been drawing. These deep carved out channels are swift and efficient.

I also noticed that the dry crumpet holes I had found across the site on the first few days had become fleeting pools of amber water, coloured by the peat being lifted before being drawn from the land and eventually into the Upper Urr River.

Because of the pace imposed by the drawing of this site it had acted as a tool to enable me to keenly notice just how severe the change to the site had been. I had absorbed it as it was before, and now it was altered. Earth had shifted, and it had changed pace in a matter of hours. The movement was astonishing.

Bogs are the essence of slowness. The movement felt within them is dulled because of its inherent nature, but the transferral across it is broad and far reaching. The entire bog moves as one, breathes as one and works as one. These carved fissures across its surface have fractured it and drained it of the vital life force that allows it to continue on its journey to archive. It cannot breathe deeply and commit to its living memory the carbon of our generation.

“Exposing record.

How much time has been revealed?

Released?

Evangeline Morris. Taken from one of the earth maps presented as the onsite research for Four and a Half Thousand years deep.

Memory

This place has a memory of carbon record. Through my time spent engaged in conversation with this place, I have seen and felt the changes brought on by interruptions to its process that threaten its stability. Witnessing these notable changes to a landscape happening so quickly that they are apparent within only six days, I found my lasting memory of this place is underscored with an anxiety about how long will we have to watch it deteriorate. With a backlog in the Carbon Credit scheme halting work to restore the bog and secure the carbon and unique environment of this place, and many more besides this one, another year at least will slip by before this peatland will be given the help to repair its fractures and begin to work as one again.

I urge anyone to take a walk through a bog. Replace your fear of these misunderstood and underestimated landscapes with the respect to ask it how to negotiate it. Feel through your feet as I have felt. Employ all of your senses through a method of conversation, be it drawing, writing, photography or just completely stopping to listen to it and through this understand this place and its magnificent actions. You will be rewarded with this humbling of our human nature, discovering an incredibly rich and wonderful place that holds the memory of hundreds of lifetimes underneath its surface.